|

You’ve likely heard about the divisiveness of the font Comic Sans. The font is not inherently bad; in fact, it’s friendly and inviting. However, the font is widely regarded as a joke, and yet it remains available to users of many word processors more than 25 years after its invention. How did Comic Sans come to be? How did it turn into such a joke? And why is it still available for anyone to use?

The invention of Comic Sans

Let’s go back in time a bit to the early days of the internet. In the mid-1990s, Microsoft was only just starting to place personal computers in people’s homes. These days, a three-year-old can pick up any smart phone and perform a number of tasks. Back in the 90s, most professionals did not know how to use a computer.

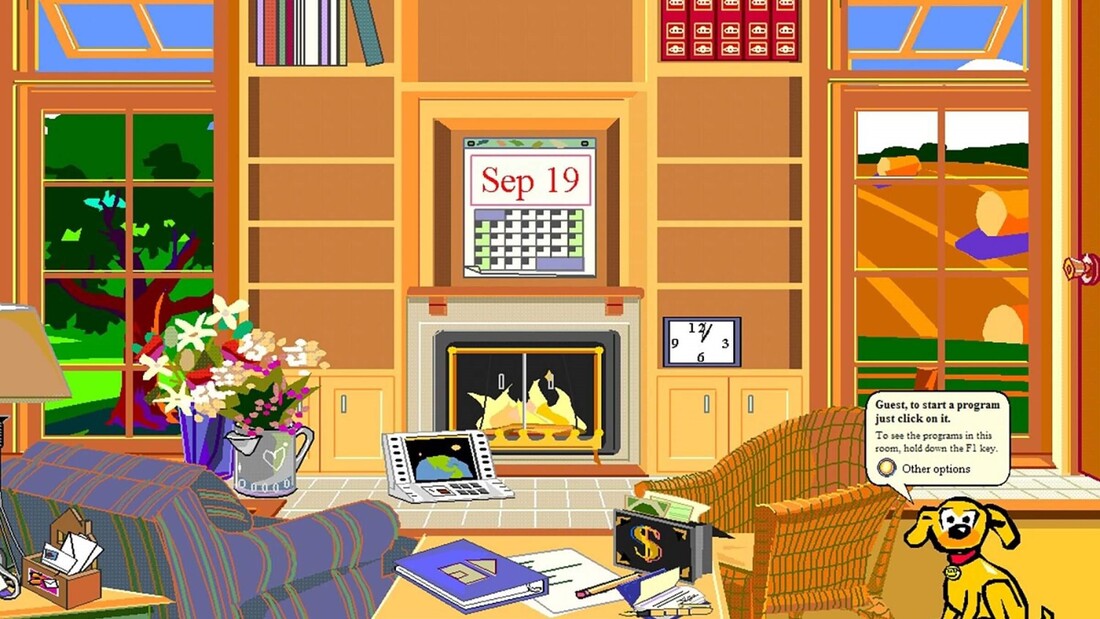

To teach private users how to interact with a computer interface, Microsoft developed Microsoft Bob. Microsoft Bob was a program that visually resembled a standard upper-middle-class home office. The idea was that connecting computer functions to the image of an office would help people to conceptualize what their computer was capable of. Characters in Microsoft Bob communicated with the user through speech bubbles, and that speech was originally set in Times New Roman.

The problem was that Microsoft Bob . . . sucked. It was clunky and unhelpful. Even Melinda Gates has referred to it as a failure.

What does this have to do with Comic Sans? Comic Sans was developed by Vincent Connare specifically for use in Microsoft Bob. He felt that Times New Roman was too stiff and formal for what was supposed to be a learning program. It was meant to emulate chunky, childish comic book fonts, and its purpose was to set first-time computer users at ease. The problem was that Comic Sans was not complete before the first iteration of Microsoft Bob rolled out, Microsoft Bob was a failure that did not last long, and Comic Sans probably should have been thrown directly in the garbage at this point. But it wasn’t. Beyond Microsoft Bob

Connare said in an interview with Ilene Strizver of fonts.com, “When I designed Comic Sans, there was no expectation of including the font in applications other than those intended for children.” Microsoft first used Comic Sans in text bubbles in Microsoft 3D Movie Maker, which was indeed designed for children. Eventually, however, Comic Sans was added to the 1995 Windows as a system font option.

Soon, graphic designers and computer users alike quickly grew tired of seeing Comic Sans everywhere, particularly in serious correspondence, where the silly font was inappropriate. In 1999, two graphic designers launched a website called Ban Comic Sans in response to being pressed to use Comic Sans for a museum exhibit design. As the internet was popularized and meme culture grew, the joke of Comic Sans grew with it. One of the most popular Comic Sans memes is the original doge meme, a series of images of grinning Husky dogs captioned with silly messages written using questionable grammar and spelling—and using Comic Sans. In 2011, Microsoft released Comic Sans Pro, which included features like italics, small caps, and more. This was released on April Fools’ Day, furthering the narrative that Comic Sans is a joke. What are fonts for?

Fonts carry vibes; there’s no getting around that. Even the most common, neutral fonts, like Times New Roman or Arial, say that the writer is straightforward, professional, and/or no-nonsense. Using audacious fonts like Chiller or Blackadder for anything real, anything substantial, says the writer is immature and not taking their project seriously. That’s the reality of fonts.

Microsoft Word can carry hundreds of different fonts, but most of the time, a regular user simply doesn’t need these. The many thousands of fonts that exist on the internet are for graphic designers to choose with much discerning. Regular people may not know what fonts look ridiculous in what circumstances, but a designer is trained to use different fonts to carefully curate a book’s (or graphic’s) aesthetic. The problem with Comic Sans is not that it exists. Wingdingz exists for some reason, so there are more baffling fonts out there. The problem with the font is that it seems like many people have no idea what kind of impression it sends, and they use it so liberally. The average internet user will see Comic Sans so much more frequently than Chiller or Blackadder. The font is specifically designed to be animated, juvenile, and silly. It kind of replicates a child’s handwriting, if they were particularly uniform and neat. Yet there are many people out there who use Comic Sans in baffling situations, like when sending an office memo or creating a resume. Comic Sans is sort of the polar opposite of professionalism, representing immaturity, movement, and failure. When scientists at CERN discovered the Higgs Boson, Fabiola Gianotti presented her results using Comic Sans. A Dutch World War II memorial was unveiled in 2012 featuring the names of Jewish, Allied, and German military deaths, all written in Comic Sans. During the UK’s great Brexit debate, the conservative party tweeted a message encouraging the parties to come together, which had been styled in Comic Sans. These are some great examples of times in which Comic Sans should not have even been considered for one moment, as its use greatly diminished the weight of what was being said. Why this is important for authors

Especially for authors who are just getting their writing careers started, nothing is more important than being professional. Publishers, editors, and even readers want to be assured that you know what you’re doing, that you’re professional, that you take your work seriously.

Particularly because typography is such an integral part of publishing a book, it’s even more important for an author to demonstrate that they have an understanding of parts of a book, including typefaces. The use of Comic Sans says, “Don’t take me seriously, and my book won’t be serious either.” What's Comic Sans good for, then?

Comic Sans is good for casual communication that is not serious, not professional, and not important. If you’re in a situation where font just straight-up does not matter, fine. Use Comic Sans. But be aware that you may be judged for it nonetheless.

There is also anecdotal evidence that Comic Sans is easier than other fonts for dyslexic people to read, though there have been no studies to support this with concrete data. However, it’s common for readers with dyslexia to prefer sans serif fonts, and the weighted sides of Comic Sans may indeed make text easier to read. There is also anecdotal evidence that Comic Sans helps writers to get rid of writer’s block, as the casual and even silly appearance of the font takes some pressure off that a writer may be feeling when writing in Times New Roman, the preferred font of publishers. This is not to say that Comic Sans is good for nothing. We are just here to beg people to stop using the font seriously, professionally, and opt for sharper options. If you’re not keen on the standard Times New Roman or Arial, try a similar variant like Garamond or Calibri. We’re happy to advise!

Sources:

https://uxdesign.cc/the-ugly-history-of-comic-sans-bd5d07f8ce81 https://www.fonts.com/content/learning/fyti/typefaces/story-of-comic-sans https://www.howtogeek.com/707340/the-origin-of-comic-sans-why-do-so-many-people-hate-it/ written by Christina Kann

0 Comments

A lot of new authors, when asked for their Facebook link, send us a link to their personal Facebook profile. What we’re looking for, and what we encourage all of our authors to develop, is a professional Facebook page. Pay careful attention to the language here -- for the purposes of this blog post, we will refer to personal Facebook profiles as “profiles” and professional Facebook pages (also known as “business pages”) as “pages.”

Sure, you already have a personal Facebook profile, so why add something else onto your plate? The answer to this question is that profiles and pages are not the same. They do not serve the same purpose, and you cannot simply trade out one for another. Let’s take a closer look at the differences between the two.

A personal Facebook profile is a great place to let your own personal audience, your friends and family, know that you have a book coming out. If you’re on Facebook personally, we certainly recommend making use of this audience. But profiles are not appropriate for professional, public author use.

For starters, unless your personal profile is “public,” your fans won’t be able to find you! The purpose of developing a Facebook presence as an author is so you can connect with fans and keep them updated about news and events. Even if your profile is “public” and fans can find you, you don’t want this kind of connection with strangers. When you accept a friend request on your personal profile, you become friends with that person in return. That means you’ll see their photos and updates in your feed, even if you have no idea who they are. They’ll also be able to see personal information that you have listed on your profile, like where you went to high school and who you’re dating -- details you may not want all your fans to know! If you have a professional Facebook page, fans can “follow” you -- meaning, they will see the updates you post on your page, but nothing you post on your profile. You will also not see any of their updates unless they directly interact with one of your posts. This is a much more appropriate creator-fan relationship. Fans aren’t your friends, lovely though they may be, and having this boundary will benefit your personal life and your professional life at the same time. You also cannot use your personal profile when collaborating with event venues, reviewers, or your publisher. For example, if we were to post on Facebook about one of our books, we couldn’t tag that author’s personal profile in our public post, because we are running a business page. If you were doing a book signing at Barnes and Noble, they could not tag you in their social media marketing efforts for that event. If a reviewer reviewed your book, they could not tag you in that review. It could lead to you missing some updates or even missing out on fans who would have followed you, if only they could! Worse, someone might choose not to collaborate with you if you’re not on social media. If a reviewer posts their reviews primarily on Facebook, and you are not on Facebook, what good does that do either of you? Even if they read the book and publish the review, they’re not getting anything out of that exchange, because they aren’t getting exposed to your audience; you’re only getting exposed to their audience. That’s not a fair trade, and lots of reviewers would pass on that sort of one-sided transaction. Furthermore, if people are searching on Facebook for “fantasy authors” or authors of your genre, you will not show up in their search if you’re only using a personal Facebook profile. In order for Facebook to categorize you in this way, you need to create a professional page and select the correct category for yourself -- in this instance, “author.” Another benefit to having a professional Facebook page you use publicly for author purposes is that you’ll look like you know what you’re doing. If someone asks for your Facebook page in a professional setting and you send them your personal profile link, it will look like you don’t understand how Facebook works, and that would affect that person’s perception of you and your capabilities as an author. Every creator these days needs to be dedicated to learning about social media -- always learning, no matter how much you know now, because social media is always changing. The bottom line is, your fans will expect to be able to find you in certain places. Just like they’ll expect your book to be available on Amazon and Barnes and Noble, they’ll expect you to have a website. They’ll expect you to be on Facebook, and possibly even Twitter or Instagram. If they can’t find you in these places, you will likely lose out on that connection, which could mean losing out on future sales or collaborations. Do yourself and your book a favor, and set up your professional Facebook page now. by Christina Kann

Whether you call it a domain name, a URL, or a web address—you know, something like www.whateverforever.com (incidentally a silly clothing line)—choosing one is almost as hard as choosing your child’s name. Your domain name is so important and will be used in so many places that it’s crucial to think carefully before committing. Moving your website from a domain you weren’t set on to a new one is a pretty involved process, so it’s better to just pick the right one in the first place!

Here are some things to consider:

by Christina Kann

You’ve written a book, you’ve agonized over edits, you’ve painstakingly written your query letter, and now—you wait. This part sucks. We get it. As Tom Petty once said, “The waiting is the hardest part.” We hope it will make you feel a little bit better to know what’s going on behind the scenes while you’re at home biting your nails.

Listen to our accompanying podcast episode!Step 1: Intake

When you submit your manuscript through our website, it goes through our submission intake process. Your manuscript submission is received through our website form, and then the submissions editor puts your manuscript in the reader queue. You will not hear from our submissions editor unless they have a question about your submission.

Step 2: The Queue

We receive hundreds of submissions per year, and we want to make sure we give every one its due consideration. This can take some time, since we accept unsolicited submissions, or submissions without an agent. We love having this open-door policy, but it does mean that our slush pile gets big! Your submission may be hanging out in the queue for a few weeks while it waits its turn.

Step 3: Review

When it’s time, the submissions editor will send your manuscript to a reader. This reader will be trained in manuscript critique and editing so they can see both the potential of your book as well as the work it needs. This reader will also specialize in your manuscript’s genre! We wouldn’t want a children’s book editor trying to evaluate the merits of a dense, adult science fiction epic.

Your reader will review your entire manuscript, or if it’s quite long, key selections. They will then consider the craftspersonship of your manuscript, its marketability, your previous works, and other variables to make their official recommendation for your manuscript. But your submission’s fate doesn’t lie in the hands of one subjective reader; next it goes to the team. Step 4: Team Decision

The entire acquisitions team will review your manuscript, your other submission materials, and the reader’s recommendation independently, and then they’ll come together to make a group decision that will work best for you, your manuscript, and the team.

Step 5: The Offer

Once the whole team has agreed, one of our acquisitions editors will reach out to you with our decision. This may be a traditional offer, an Emerging Authors invitation, a self-publishing offer, or an outright rejection in some rare cases.

It’s up to you what to do next! We are so grateful for the submissions we receive, and we’re lucky to be able to review every single one, whether the author is represented by an agent or not. We understand that waiting for a publisher’s decision can be agonizing, so hopefully, understanding all that goes into this process will help encourage your patience. We can’t wait to check out your manuscript! by Christina Kann

Our entire editorial team had the exact same experience with style guides before entering the publishing industry: we used style guides to format citations for papers in college, and nothing more. If you’re like us, then perhaps you, too, had no idea that a style guide was intended for anything else.

In fact, style guides are massive, complex, and crucially important -- and we barely ever use them for citations anymore (lookin’ at you, nonfiction!). A style guide is a rulebook for writing that outlines grammar prescriptions and recommendations that can also give advice for troubleshooting unusual issues. Listen to our accompanying podcast episode!

Style guides are used to ensure that every publication coming from the same place uses the same grammar system. For example, essentially all fiction books that are published in American English these days are edited using the Chicago Manual of Style (CMS), which the University of Chicago Press has been publishing since 1906. (Students sometimes use Chicago/Turabian, which is a streamlined version of CMS for academics.)

You may recognize some of the hallmarks of CMS, like a preference for the Oxford (or serial) comma. As editors, we rely on CMS to tell us where commas go (spoiler alert: it’s complicated!) and how to format ellipses. . . . It also tells us what order parts of the book go in. For example, CMS prefers that the dedication page of a book goes in the front, while the acknowledgments page should go in the back. CMS also defers all spelling questions to Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary in particular! Some other style guides may be familiar to you, like the Modern Language Association (MLA) style guide or the AP (Associated Press) style guide. Many companies and other organizations also develop their own style guides. These corporate style guides can come in handy when a company like Medium, for example, utilizes hundreds of writers from all around the world but still wants all those articles to be grammatically consistent. That’s the key word here: consistent. The entire purpose of style guides is to ensure that a book’s grammar is consistent throughout; that an author’s books are consistent from one to the next; that a publisher’s book list is edited to a consistent standard; that books across the country are grammatically consistent so readers have an easier time hopping from one to the next. Having a codified system that any editor can turn to, via print style guide or online, is how we achieve this glorious consistency. All this is to say: Your editor is not making up their grammatical recommendations. If you have a really nice editor (say, any editor at Wildling Press), they may take the time to explain some of their corrections to you using CMS as their guide. However, just like any other industry, these rules are complex and layered, stacking on top of each other to create a full spectrum of meaning and clarity. It’s not always easy for an editor to explain why they’ve made a certain correction. But more often than not, there is a grammatical rule (or several!) from CMS behind their correction. Studying the CMS is a great step to take to become a better writer. We once had someone tell us, “I’m not familiar with CMS, but I could read it in a day or two.” Well, they certainly missed the point! Reading the style guide from cover to cover might not do you much good -- unless you have a really excellent memory for that sort of thing. Instead, try evaluating the choices you are making when writing, and then asking yourself, “Why am I making this choice? Is this the right choice?” Before you slap that comma there, try looking it up! Does a comma actually belong there? (As we mentioned, commas are really objectively unreasonably complicated.) Here’s the good news: if working with a style guide is hard for you, you can rely on your editor to show you the way. Just be sure to remember that their corrections come from a good place: the Chicago Manual of Style! by Christina Kann |

How Do I Book?We'll try to find the answer to that question in our blog. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed